Tabasco Batting

White-winged Vampire Bat, Diaemus youngi

Back in those halcyon days, before the collective name for a group of caution was “an abundance’ and when “social distancing” might describe me during conference coffee breaks, I went to Tabasco for a weekend’s batting. As always I teamed up with Juan Cruzado. And – as nearly always – I followed in Venkat Sankar’s footsteps, inspired by the Tabasco portion of this trip report.

Juan, a biologist, has an encyclopedic knowledge of Mexico’s mammals and where to find them. He also has a huge network of contacts around the country and this time we teamed up with Kristell Gracia, a student from the University of Tabasco studying the Common Vampire Bats in the caves near the small town of Tacotalpa.

One of the bat caves

Winter is the best time to visit, But it was unseasonably wet while I was there, which – coupled with long nights netting inside the massive cave system – meant I barely looked for other mammals. Most of the day was spent sleeping in the hotel, and most of the night inside the caves.

I had three main goals: the tiny Thomas’s Sac-winged Bat, the impressive Tomes’s Sword-nosed Bat and the very rare – and super cool – White-winged Vampire Bat.

The sac-winged bats are abundant: by far the commonest species in both of the caves we netted in and we saw hundreds.

Thomas’s Sac-winged Bat, Balantiopteryx io

The other two species are much harder to see. Juan, Kristell and I divided our time and nets between two caves. One offered the best chance of a sword-nosed Bat. The other the best chance of a White-winged Vampire.

THomas’s Naked-backed Bat, Pteronotus fulvus

Both these species are rare here and hard to catch. The White-winged Vampires in particular, which are also late flyers and typically do not emerge from the caves until close to midnight. So we had plenty of time to wait and catch other bats.

Sac-winged bats aside we caught one Thomas’s Naked-backed Bat, a Mesomamerican Common Moustached Bat many Common Vampire Bats.

Common Vampire Bat, Desmodus rotundus

The caves we netted are interconnected and the chambers run for hundreds of meters, though water and mud meant it was only possible to explore the first hundred meters or so of the two caves entrances. We saw three species roosting near the entrances of the caves: Thomas’s Sac-winged Bats, Common Vampire Bats and a few Jamaican Fruit-eating Bats.

Jamaican Fruit-eating Bat, Artibeus jamaicensis

We also caught a Great Fruit-eating Bat.

Great Fruit-eating Bat, Artibeus lituratus

We did not catch a White-winged Vampire Bat or a Tomes’s Sword-nosed Bat during our first two nights netting (both of which lasted until 3 a.m). On our last night we had to pack up at midnight, as I had a fairly early start to catch a plane home.

At 11.55 p.m as we were starting to pack up our gear a large bat flew into the net. Jose let out the sort of cry usually reserved for someone taking their first parachute jump and I realized what had happened. A vampire bat in the net. And one that looked a bit different.

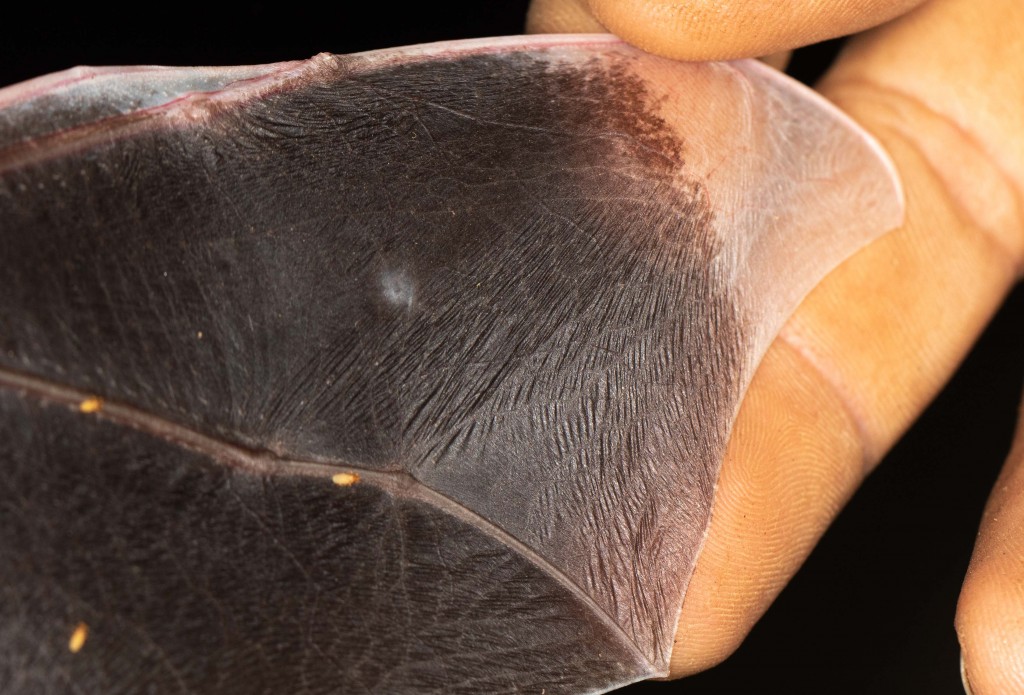

Could it be …. yes! The white wing tips confirmed it. A lifer for both Jose and me. My most wanted bat in the neotropics. Probably the world now I think about it.

White-winged Vampire Bat, Diaemus youngi

This is an extraordinary species. They have scent glands in their mouth that secrete a foul smelling odor. And they have especially large brains in proportion to their size, perhaps because of – or the reason why they can have – such advanced foraging strategies. These are stealth hunters. They look very like Common Vampire Bats at first glance, but with larger eyes they are cuter. A bit cuter anyway.

White-winged Vampire Bat, Diaemus youngi

We packed up the nets delighted with our last minute luck. Three nights of foreplay made the sighting so much better.

Earlier that evening we set up alongside a small river near the cave mouth and caught a single Western Long-tongued Bat, another lifer for both Jose and me and best distinguished from other long-tongued bats by their incisors.

Western Long-tongued Bat, Glossophaga morenoi

The rain stopped on the last night so we set a few Sherman traps at midnight and the next morning caught three rats. At the time we thought they were Peter’s Climbing Rats, a species Jose commonly sees inside the caves here. But – thanks to Fiona Reid and others – we now know they were Big-eared Climbing Rats.

Big-eared Climbing Rat, Ototylomys phyllotis

Other than that the weekend’s mammal list also included Common, Virginia and Northern Four-eyed Opossums (now split as Philander vossi from P. opossum) crossing the road at night.

Thank you to Juan and Kristell for their patience and hard work. Great to be able to support the bat research for a weekend and have so much fun in the process.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.