Nunavut Including Baffin Island

Polar Bear, Ursus maritimus

In 1999 the new Canadian province of Nunavut was carved out of what was then the North West Territories. It is an extraordinary place: one of the few places I’ve been that makes the Australian outback feel crowded. Nunavut covers about a fifth of Canada (so its about the same size as Western Europe) but has a population of just 29,000 people, 85% of whom are Inuit. There are about six trees, otherwise the entire province is tundra.

And it is seriously cold. It can drop below -50 C in winter, though in July the average maximum temperature is a sweltering 8 C. Oh and it is stunningly beautiful and home to some spectacular mammals.

Baffin Island, near the North West Passage

There is good mammal watching to be had in many parts of Nunavut, but most people head to Baffin Island, at least for their first visit. Baffin is the place to see Narwhals, has a stack of Polar Bears, along with just about all of the other species you’d expect from the eastern arctic. And although Baffin is pretty remote, it is somewhat better set up for ecotourism than many other bits of Nunavut. I’d long wanted to visit, and I finally got there in June 2006.

Northern Baffin Island

The Basics

If you want to see a wide variety of the Baffin wildlife then you’ve two main options: take a cruise around the island; or take a land and ice based trip to the edge of the ice floe, where the sea ice meets the open ocean. The floe edge trip typically involves camping on the sea ice for four or five days and traveling by snow machine and komatic (sled), And it is the more ruggedly authentic arctic experience, and probably offers a better chance to get close to animals like Polar Bears and Narwhals. But you will likely see a greater diversity of mammals from the deck of a cruise ship.

Although the cost of getting around on Baffin is not stupendous, the cost of flying there from Ottawa is insane. I don’t know any way around this.

Most visitors come between late May and late August. There is 24 hour daylight, a reasonable chance of decent weather (with ‘decent’ being relative to the rest of the Baffin year, not Hawaii) and this is the only season that you’ll have a hope of seeing things like Narwhals. Floe edge trips usually run only from late May through early July, from when the floe edge first opens up, to when the sea ice melts. Cruises run a bit later in the season. Between June and August some local operators offer other trips including kayaking expeditions or boat-based Walrus and Bowhead Whale watching.

Polar Bear, Ursus maritimus

Floe Edge Trip, June 2 – 9, 2006

The floe edge – where the sea ice melts into the open ocean – starts opening up off north Baffin in late May. By early July the sea ice is melting fast and traveling across it can be dangerous. Wildlife gathers along the edge: whales and seals are attracted by the fish and krill feeding in the nutrient rich water; polar bears are attracted by the seals. Floe edge trips leave from Pond Inlet: day trips are usually possible though I’d arranged to take a week’s package through Polar Sea Adventures.

Long-tailed Jaeger

On Friday June 2 we flew into Pond Inlet from Ottawa, via Iqaluit on a scheduled First Air flight. Pond is a small, apparently happy and globalised community. Snowmachines and satellite dishes brush shoulders with huskies out on the ice, and bear skins stretched out to dry. I heard stories of the local Inuit heading out to hunt Narwhals in the traditional way, and returning to town to sell the tusks on Ebay.

Pond Inlet

Much of what happens on Baffin is governed by the ice conditions, and this trip was no exception. Trips generally head to the floe edge east of Pond, about three or four hours by snowmachine. But in early June 2006 there was no floe edge there. And so we had to take a ten hour trip to the northern tip of Baffin, where the satellite pictures showed a more promising floe edge was developing.

And so it was that eighteen of us – 10 paying, 8 paid or working voluntarily – set off at around midday the next day. We were divided between five snowmobiles and the komatics (sleds) they pulled. I can’t remember a more scenic, or colder, 10 hours. And words cannot do justice to the views or the numbness in my fingers.

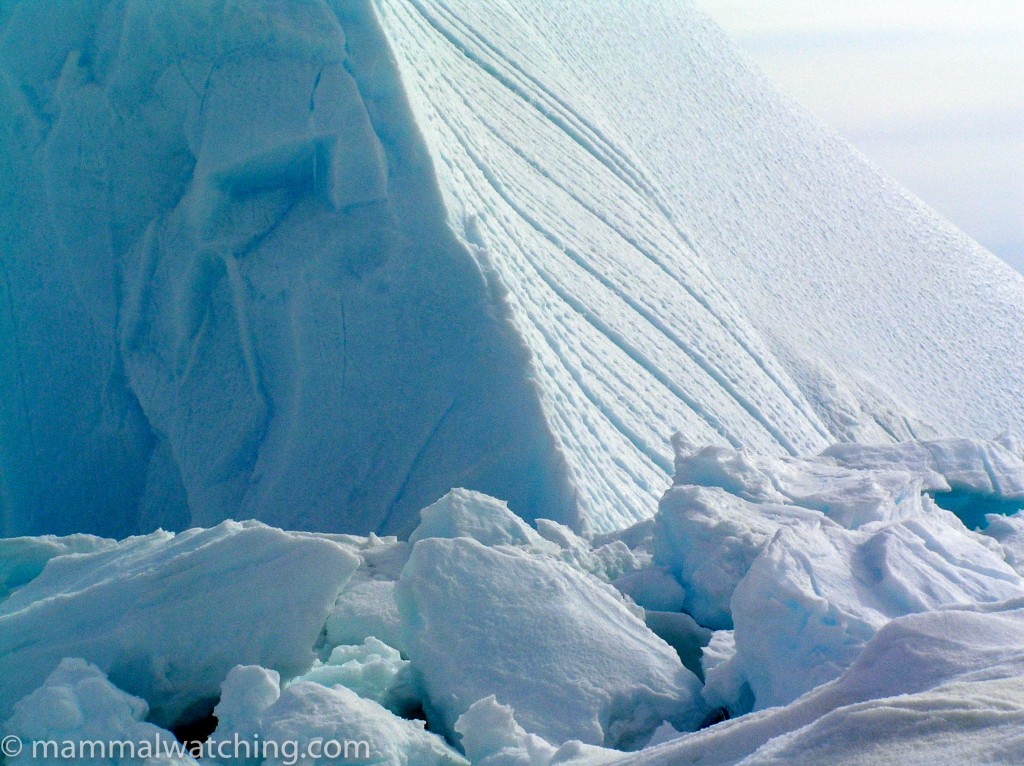

We set up camp below an abandoned research station, pitching our tents on the sea ice. And it was here that we spent the next five days and nights. From the cliffs above camp we could see a floe-edge of sorts a few kilometres away, but there was at least a kilometre of rough ice between us and the ocean; ice too rough for the snow machines to get through. But the floe edge changes quickly.

There was no particular routine over the next four days, with plans changing according to the weather. Because the floe edge, and often the weather, wasn’t co-operating, we spent time looking at icebergs, walking along the cliffs, watching bears, and sheltering from force 10 gales, driving rain and snow. But during our last day the floe edge opened up and we managed to find a path through the pack ice, to get within earshot of the Narwhals. I’ve listed some details of the mammals we saw in the next section. But first a few general observations about the trip.

Camping on the sea ice

I was surprised by the number of bears we saw (at least 10 separate animals, probably more), and how dangerous they are considered to be. We mounted a 24 hour bear-watch at camp, with loaded rifles strategically positioned. This approach struck me as somewhat over cautious until I better understood how large a 4 m long, 800 kg carnivore really is when you see one up close. And then I heard some of the local’s bear attack stories. They are fast, sneaky and not at all scared.

Polar Bear, Ursus maritimus

Given the number of bears around, the guides were understandably reluctant to let people wander off. That makes perfect sense, though it was also a bit frustrating. If you are keener than the rest of the group to go off and look for the local fauna you might have to make do with using your binoculars from the campsite, or in my case wander up to the research station above camp every now and again, to risk life, limb and a lecture.

The old research station above camp

My first polar bear was a special moment; an hour that will stay with me forever. And that hour alone made the entire trip worthwhile. The bear patrol in camp had seen a couple of animals during our first night on the ice. The guys hadn’t woken me up so I vowed to stay awake on day 2 until I’d seen one. At about 1 a.m. one of the Inuit guides – the older of the two Abrahams – wandered over and asked me if I wanted to go chasing a polar bear. It was a tough decision, me being near the end of a good book and all, but thirty seconds later I was on the back of a snowmachine, clinging to Abraham’s jacket, my camera and dear life.

We headed in the general direction of the bear he’d seen from his vantage point on the ridge above camp. Fifteen minutes, maybe 10 km, later we spotted the young male bear he’d seen. The bear stopped periodically to sniff in our general direction, but otherwise seemed untroubled to see us. In fact his relaxed air, and general inquisitiveness had him wander to within 50 metres of us. It was around about then that Abraham wondered whether ‘inquisitive’ might also mean ‘hungry’, and he announced with considerable urgency that we should go.

We saw plenty more bears on the trip but this first encounter – just me, Abraham and the bear, above the sea ice and under a midnight sun – was pretty much the perfect arctic moment. Life seldom gets better than that.

My first Polar Bear, Ursus maritimus

The air was very clear. So much so that I had problems working out how far things were away, something the early arctic explorers also noted. This adds a surprising layer of complexity to mammal watching. For instance, on my first morning I saw a white lump moving on the ice about 3 km away: must be a Polar Bear! But when I lifted my scope I saw nothing more than a Glaucous Gull. That distant white lump was in fact only 300 m away. It really did feel impossible at times to work out even approximately how far away things were.

Floe Edge

When the floe edge finally opened up on the last day my expectations were fulfilled. We had pods of Narwhals moving past every 15 minutes or so, sometime just 100 metres off the edge of the ice (but 500 metres from us, because we hadn’t found a way to get the snowmachines through to the very edge). Standing on top of an ice-locked iceberg, watching pods of Narwhals through the scope, and hearing them blow was another quintessential arctic moment.

I just saw a Narwhal! (photo Ken Balderson)

I wish we’d had the conditions to spend more time doing this. If we had I am pretty sure we’d have had a decent chance of finding Bearded Seals, Walruses and Belugas as well as better views of Bowhead Whales. Some trips have the ice conditions to get to the very edge of the floe, and presumably within tens of metres of passing Narwhals.

Iceberg

An enormous quantity (40 million tonnes) of iron ore has been found on Baffin and plans are underway to mine it. In 2006 this was still at the planning stage but clearly it has potentially huge effects on the island and the islander’s way of life.

And finally, the people working on the expedition were all good at their job and great company. In particular the four Inuit guides – Panuili, the two Abrahams and Jason – were fabulous to spend time with.

Abraham, Abraham, Jason and Panuili (left to right)

The Mammals

Before I got there I was frustrated by the general lack of information about what I might and might not see on the floe edge trip. The following is a summary of what I found out when I arrived.

In June at least, Ringed seals are the common pinniped, and you’ll see them in small groups across the pack ice and at the floe edge.

Ringed Seal, Phoca hispida

Bearded seals tend to stick to the floe edge, where they are present if uncommon. We didn’t see any, though we had relatively little time at the floe edge. Harp Seals are quite uncommon on floe edge tours, but are regular later in the summer. Hooded Seals are just plain rare.

Walruses prefer shallow water. They are sometimes seen at the floe edge on the northern tip of Baffin (where we camped) but not often at the floe edge near Pond Inlet and Bylot Island. In other areas, near Hall’s Beach and Igloolik for example, they are quite easy to find.

Arctic Hare, Lepus arcticus

We saw only a few Arctic Hares, including one individual that was living in an upended 40 gallon drum on the abandoned air strip above our camp. They are seriously weird animals, with their bouffant bodies and stick legs, strange gait and penchant for standing up straight on their back legs. Arctic Foxes are not all that common either. At least one person in our group saw one, during the long trip back to Pond Inlet from camp, and we saw tracks near a couple of bear kills. I imagine they are easier to see near sea bird colonies.

Arctic Hare, Lepus arcticus

Caribous and Wolves are two mammals that are not often seen on either cruises or floe edge trips, but would probably be easy enough to find if you spoke to the locals.

Polar Bear, Ursus maritimus

I saw many more Polar Bears that I was expecting. We saw them every day, usually more than once. They tend to be more active in the cooler parts of the day and night. While most were distant we got to within 50 metres of two. They can move at surprising speed.

Polar Bear, Ursus maritimus

We mainly several lone bears and at least two mother and cub pairs. From what I can tell, we were in the bear capital of Baffin. Bears are usually seen on the floe edge trips closer to Pond, but they are less common.

Collared Lemming, Dicrostonyx groenlandicus

I didn’t see any Lemmings until I got back to Pond Inlet. They are common in Pond, particularly around the old rubbish dump where both species (Collared and Brown) can be found lurking under bits of old metal and wood.

Brown Lemming, Lemmus trimucronatus

If you can’t find the Lemmings don’t despair: simply offer the local kids you meet $10 for whoever catches you the first lemming. A posse of zealous lemming hunters will quickly gather. They were effective but a little over eager, and for the next 12 hours a procession of kids arrived at my hotel clutching lemmings and wanting to claim their finders fee.

Lemming Hunters

There are no Musk Oxen on Baffin. But they are easy to see in other bits of Nunavut, such as Devon Island, and Greenland. They are apparently easy to see in these places; but these places are not so easy to get to.

The three key arctic cetacean species off Baffin are Narwhals, Bowhead Whales and Belugas. Narwhals are pretty common all along the floe edge. We saw plenty during what little time we had near the water.

Narwhal, Monodon monoceros. Pond Inlet Floe Edge (Abraham Kublu).

Bowhead Whales are less common but they are around and are probably commoner on the northern floe edge. I had distant views of at least one animal – but too distant to class as tickable.

Belugas were reportedly more common on the northern floe edge than nearer to Pond. Or so I was told. Having said that we didn’t see any on the northern floe edge, but the trip the following week to the Pond Inlet floe edge saw heaps.

Listening to Bowhead whales on the hydrophone

From the trip reports I have read, the cruises around the eastern Arctic usually see all the mammals we saw on the floe edge trip, together with Bearded, Harp and sometimes Hooded Seals and Walrus. These cruises don’t seem as good as floe edge trips for seeing Belugas or Narwhals.

Polar Bear skeleton

In August Polar Sea Adventures run 2 week sea kayaking tours with good chances of seeing Narwhals.

Igloolik

Igloolik lies off the northwest coast of Baffin. Though most of the floe edge trips on Baffin are sold as a package, I don’t see why it wouldn’t be possible to prearrange add on trips. This is particularly worthwhile when you realise that a very large portion of the expense in visiting Baffin is tied up in the airfare from Ottawa. Walruses, for example, should be quite easy to see at any time of year near Igloolik, with Bowhead Whales and Bearded Seals in the area too from mid June to mid July. Bowheads return in August, and Narwhals and Belugas arrive then too.

You can fly from Pond to Igloolik direct several times a week for a couple of hundred bucks (rather than the mega expensive option of flying through Iqaluit). I imagine there are local outfitters in Iglooik who could make arrangements.

Community Reports

The World’s Best Mammalwatching

In early June the Baffin sea ice starts to melt. The edge of the ice floe is a meeting ground for Narwhals, Polar Bears and a host of Arctic wildlife. This is one of the greatest – and most adventurous – wildlife destinations in the world and I was lucky enough to visit in 2006. Polar Sea Adventures organised the trip and did a wonderful job. See more of the World’s Best Mammalwatching.

Nunavut Cruise, 2014: Dominque Brugiere, 13 days & 10 or so species including Polar Bear, Bearded, Ringed and Harp Seals and Walrus, Musk Ox , Narwhal and Bowhead Whales.

Arctic Bay, 2014: Cheryl Antonucci, 8 days & 8 species including Polar Bears, Belugas, Narwhals & Bowhead Whales. Stunning images.

Arctic Canada, 2004: Richard Webb, a 2 week cruise & some nice mammals including Hooded Seals, Walruses and Narwhals (this file is a bad quality scanned bitmap file).

Also See

RFI Baffin Island, August 2024

Jeff Higdon’s comment here has some useful advice on Baffin mammals, July 2024

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.